Psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia are as much the result of disease processes as are somatic diseases such as pituitary adenoma or tuberculosis. As such, they deserve the same diagnostic strategies and consideration of appropriate somatic treatments (e.g., medication). Most of these psychiatric diseases affect a patient’s sexual functioning.

In the initial diagnostic stage of treatment, the disease perspective alerts the clinician to exhaust empirical medical data provided by the presenting problem and gathered in the patient’s history. A recent physical examination is necessary for any disorder that may have somatic roots. Dr. M.’s knowledge of Sally’s behavior was grounded in a careful history taking, which indicated that a major mental illness had afflicted the patient’s mother. While certainly the illness could have affected the mother-daughter relationship in many ways (e.g., making the mother less emotionally available), Sally’s bipolar disorder might also have genetic components.

The disease perspective correspondingly alerts the clinician not to rush prematurely to establish an etiology rooted in a “meaningful explanation” of the problem. For example, it would be facile to attribute Sally’s behavior to some fault in the marriage or to personality factors such as inappropriate dependence on male approval. Indeed, almost all depressed individuals attribute their depression to life situations, in an understandable attempt to develop a rationale for the way they feel. It is much easier to say “I am depressed because of the way my life has gone recently” than to say “While things have not been perfect, all in all everything has been going as it usually does. It is just that my depressed mood has a life of its own. My neurotransmitters must not be working properly.” The former is an attempt at a meaningful explanation (to be examined in the life story perspective), while the latter is a (rarely heard) appreciation of the depression from the disease perspective.

The disease perspective is, as would be expected, the main perspective of schools of medicine and nursing. These graduate programs stress the need to observe carefully and exhaustively the various somatic phenomena in a person’s complaint as well as the medical history that he or she provides. Medical graduate programs teach their future clinicians how to conduct a review of organ systems and mental status examinations. Personal and family medical histories yield information about past diseases, surgeries, and medications.

Graduate schools of psychology and social work often do not share this emphasis. In these disciplines, the circumstances of intrapsychic, interpersonal, and social environment are valued highly and therefore often described in minute detail. Attention may be paid to personal and family medical and psychiatric histories. There is less likely to be a recording of the complete regimen of medications with accurate dosage. And conducting a mental status examination—with its attention to factors such the patient’s appearance, neurovegetative symptoms, manner of speech, thought processes—is usually an indication that the psychologist or social worker has been trained in a medical or residential facility.

Whereas medical and nursing students may overlook the psychological and relational factors in the patient’s disease, social science students, especially with the advent of social constructionism, may overlook the role of the body and the body’s diseases in the etiology of the problem. The disease perspective, then, is the familiar territory of the physician, nurse, and medical clinician. It is the terra incognita of the psychologist, social worker, and counselor, unless efforts are made to learn more of this “body” of knowledge. Thus, the role of the disease perspective should be supported and nurtured by the psychologist, social worker, and counselor by developing relationships with medical practitioners, including psychiatrists, who can supplement their psychological skills with medical knowledge of the body and its diseases.

It is not always easy to see the connection between a sexual behavioral pattern and a disease process. Often this is because we notice the behaviors as a syndrome and correlate them with a psychiatric disorder that is not yet proven to have a pathological process in the body (brain). The case of Sally is helpful here.

Sally was a 43-year-old married woman whose husband was employed as a utility repairman. It was the second marriage for him and the third marriage for her. Together they had no children, but she had two daughters (ages 20 and 18) and he had a son (age 14) by previous marriages. She worked as a clerical staff person in a construction company.

They sought marriage counseling in crisis because Sally had had a sexual relationship with a neighbor, the father of one of her stepson’s friends. In the initial history, Sally reported that she had always felt she had a higher sexual drive than other women she knew. She judged herself to be slightly better than average in appearance, and she thought she often “gave off vibes” to men that she was sexually interested in them, even though they had met only casually. She said that men usually responded to her, and it was not difficult to conclude a casual meeting with a sexual encounter. Sally judged that she had had approximately thirty to thirty-five sexual partners in her life, all of them men, except once when she engaged in a mйnage а trois with a man and a woman.

Sally described most of the sex as involving little knowledge of the other person but very intense in terms of sexual drive and pleasure. She felt that the men were interested in sex also and that neither they nor she sought any lasting or committed relationship. She said she loved her husband and did not want the recent sexual wandering to ruin the marriage as it had in the two previous marriages. She wanted this time to be different and was convinced that it would be.

In her initial history-taking session with Sally, Dr. M. took a complete and careful sexual history and a detailed mental status examination. From both the history and the present mental status, Dr. M. concluded that Sally’s episodic high drive correlated with other symptoms of a bipolar II disorder.

On closer examination of the sexual encounters, Sally was able to see that there was an episodic quality in the frequency of the behaviors. For months she would have what she felt was low (for her) sexual desire and interest, and then a period ranging from four to six weeks when she would become, in her words, “sexually alive.” Also during these periods of being sexually alive, Sally would have a great deal of energy, undertaking exercise programs, requiring little sleep because of all she wanted to accomplish, and, on occasion, spending to such a degree that she “maxed out” her three credit cards. During these periods, she felt as if she got along very well with her husband, although the spending caused arguments.

Sally could not describe her mood and energy level during the times between these periods of elevated mood and energy. The best she could do was to say, “It’s kinda like I feel now, since the discovery of my sexual time with N.” In the mental status examination of her present mood, Sally reported that she felt tired and was not sleeping well—which she attributed to her worries that the marriage might be breaking up. She had lost eight pounds in the past month and wanted sex with her husband only to help keep the marriage going, not because of any sexual desire or interest on her part. While she felt somewhat guilty about the sex with her neighbor, it was difficult for her to distinguish the guilt about the behavior itself from the deep regret that the trysts were discovered and her marriage threatened.

Dr. M. learned other facts about Sally that confirmed her diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. Although Sally had never received treatment from a psychiatrist or other mental health provider, her mother had been hospitalized on three occasions. The first time occurred in her mother’s early twenties and the diagnosis was schizophrenia. The last two hospitalizations had occurred within the past twenty years, and her mother was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and alcohol abuse. For the past seven years her mother had done well, avoiding alcohol and being maintained on a regimen of lithium carbonate and, more recently, Depakote (valproic acid) to keep her mood stable.

With the familial factor of affective illness, and the carefully obtained psychiatric history, Dr. M. concluded that Sally’s sexual behaviors were caused, in large part, by her affective illness. The bipolar II disorder increased her libido and diminished her ability to judge the appropriateness of her behaviors, both sexual and financial. At the time of her sexual escapades, Sally clearly had only a vague awareness of the consequences that her behaviors might have on her life and on the relationships she valued.

Dr. M. recommended both psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment. Because Sally’s mother responded well to Depakote, Dr. M. started Sally on that medication, in addition to a serotonin-specific antidepressant for her present depression. The psychotherapy had two goals: to understand Sally’s vulnerability to the excesses of bipolar disorder and to “make some sense” of the prolific sexual experiences she had had in her life.

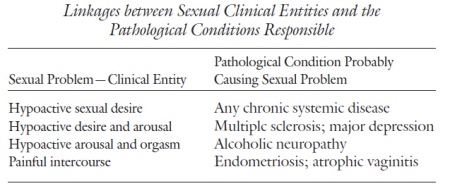

Application of the disease perspective to sexual disorders is the work of ensuring that the somatic factors, disease processes, and physiological functions, as they may relate to the cause or expression of the sexual disorder or dysfunction, have been identified. It entails linking the clinical entities with a pathological condition. In sexual problems, the clinical entities of the sexual dysfunction and the patient’s medical history may indicate the pathological condition. The linking of the two is the task of the disease perspective. Table lists some common linkages between sexual problems (clinical entities) and medical illnesses (pathological conditions).

Treatment in the disease perspective is to cure the disease or, when that is not possible, to alleviate the symptoms. When sexual dysfunction is present as a helpful sign or symptom (clinical entity) of an underlying pathological condition, treatment is given to address the pathological condition. When one cannot successfully treat the underlying condition (e.g., peripheral neuropathy), symptomatic treatment is given (e.g., oral medication for erectile function). Another clinical case can illustrate the work of the disease perspective.

■ Ralph was a 45-year-old man who had enjoyed a twenty-year marriage with his wife. Their three children, now in their teens, added no more than the usual amount of Sturm und Drang of adolescence to the household. Ralph had been in sales throughout his career and presently was making another shift in employment—this time to assume major responsibility for a national product line.

Ralph was in apparent good health, although slightly overweight. He drank one beer daily with his main meal and exercised infrequently. In their sexual life, Ralph and his wife had usually had intercourse about three times a month and neither had experienced sexual dysfunction—until recently.

For the past several months, Ralph had noticed himself becoming less and less interested in sex. The frequency of intercourse had decreased, and he had not wanted to have sex for the past two months. Sexual thoughts and fantasies were absent. While he had masturbated on occasion in the past, this behavior was absent in the past six months. He noticed that he and his wife were not getting along as well as usual, and more frequently than in the past were “getting on each other’s nerves.”

Ralph consulted his physician, who ordered a serum testosterone level and liver function tests on the suspicion that Ralph had underreported the amount of his drinking and, in fact, may have reduced testosterone due to his alcohol consumption. The physician also assessed Ralph for depression. Other than being upset by his low libido, Ralph gave no indication of being clinically depressed. Even the strain of the transition to the new position at work was evoking in Ralph his typical “can do” optimism.

The serum testosterone level came back remarkably low. This explained the low sexual desire. But more remarkably, the pituitary (prolactin) level, measured at the same time, was correspondingly elevated. Ralph’s physician suggested that he have an MRI to check for any lesion on his pituitary gland that might be causing the hyperprolactinemia.

The MRI reading came back positive. Ralph had a pituitary adenoma, a nonmalignant neoplasm on his pituitary gland. He began a regimen of bromocriptine. After several months’ treatment, his levels of prolactin and testosterone had returned to normal. With the return of normal levels, Ralph regained his premorbid baseline of intercourse once a week.

Two years later, Ralph and his wife are back to enjoying sex at a frequency of about once every ten days; he has again switched to another company; and only one of the three children has gotten into academic trouble. In short, things are back to normal.

The disease perspective is the perspective most often used by physicians. For this reason, application of the disease reasoning process to psychiatric or behavioral disorders is often referred to, disparagingly, as the “medicalization” of psychological problems. Is this a fair critique?

If, in fact, the disease perspective is the only reasoning method in the mental health clinician’s armamentarium, then his or her diagnostic reasoning will be reductionistic. But attempting to understand all problems as ultimately rooted in a bodily disease is not the disease perspective’s rationale. As I will repeat often in this book, a particular perspective—in this case, the disease perspective—is but one way to understand and sometimes even causally explain a disorder. Ralph’s case is a good example of this.

Ralph’s low libido was the symptom that disturbed him (and his wife) and alerted the physician. He clearly was not as interested in either thinking about or having sex as he had previously been. While Ralph’s low desire might have been attributed to a combination of aging, alcohol consumption, pressure at work, and tension at home, his physician ordered the proper tests. The low serum testosterone was the abnormal hormonal function responsible for his reduced sexual desire.

The physician then sought to explain why the testosterone level was so low. He discovered that high prolactin levels, hyperprolactinemia, were suppressing it. But what was the underlying cause of the high prolactin? The MRI indicated that a small, benign tumor—an adenoma— was growing on Ralph’s pituitary gland, located deep within the subcortical area of his brain. Fortunately, surgery was not indicated and Ralph responded well to the oral medication. If the disease perspective had not been employed here as the primary diagnostic and treatment perspective, then an expenditure of many months and dollars, and perhaps a further deterioration of the relationship between Ralph and his wife, might have followed. Hours of sexual or marriage counseling might have been spent on asking how much did Ralph really drink, were husband and wife taking each other for granted and not communicating well, was Ralph too involved in his work? While all these questions might be worthy of attention, it would have been a major therapeutic error to think that addressing them and attempting to make changes in these areas could have any substantial effect on Ralph’s sexual desire. In addition to low libido, therapy-induced frustration would have been added to the symptom cluster.

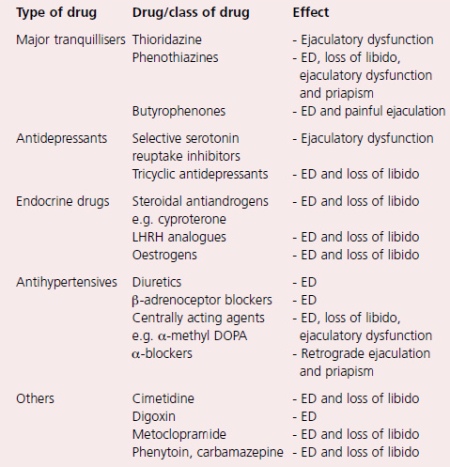

A large number of drugs can impair sexual function, either by an effect upon erectile function, ejaculatory function or sex drive. Some of the more commonly used drugs are listed in table. Use of these drugs very rarely produces ED on their own, their action usually being an adjunct to another pathophysiological mechanism.

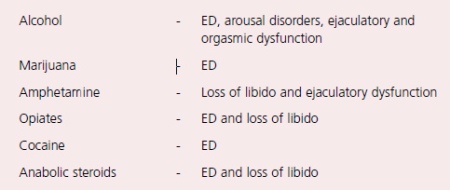

The sexual effects of recreational drugs are shown in table. Surgery and radiotherapy can also impair erectile function.

The commonest surgical cause of ED is radical pelvic surgery for rectal cancer, bladder cancer or prostate cancer. The parasympa- thetic nerves that subserve penile erection run adjacent to the prostate and are often damaged during such radical surgery. Techniques of surgery (in particular radical prostatectomy) have been devised with the aim of both nerve and potency preservation.

Other surgery that can lead to ED includes spinal surgery and surgery for Peyronie’s disease or for priapism, while radiotherapy for bladder, prostate or rectal cancer will often lead to delayed ED via a vasculogenic mechanism.

Conclusion

The pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the development of erectile dysfunction are many and varied. A number of mechanisms may be active in an individual, and nowhere is this more true than in men with diabetes. Around 50% of diabetic men can expect to develop ED, and pathophysiological mechanisms involved include peripheral autonomic neuropathy, large vessel atheroma, small vessel microangiopathy, endothelial dysfunction and psychological disorders.

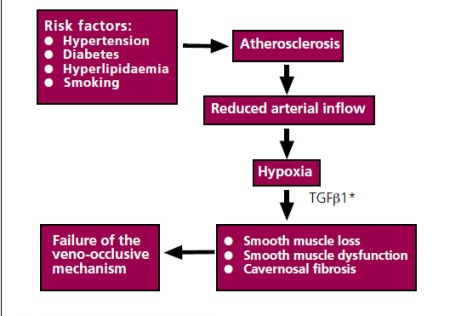

In the general population, the commonest causes of ED are vascular, and there is increasing evidence that the risk factors for atherosclerosis, namely hypertension, smoking, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes, are all strongly associated with ED.

This has two important consequences.

- Firstly, control of these risk factors might be expected to reduce the risk of ED.

- Second, when men do present with ED, it is important to identify these risk factors, not only to potentially improve the ED, but also to try to prevent other future cardiovascular sequelae.

Vascular disease is probably the most common cause of ED, and of all the vascular causes, the commonest is atherosclerosis. However, not only is atherosclerosis associated with ED, but its risk factors, namely smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes, are also associated with the development of ED. The Massachusetts Male Aging study described an association between ED and hypertension, diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia. The Cologne study of men with ED also confirmed an association between ED and diabetes and hypertension, while several studies have demonstrated an association between smoking and ED. At a cellular level, it has been suggested that a reduced arterial inflow leads to relative hypoxia within the penis with subsequent cellular effects. The crucial cellular mediator appears to be Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 (TGF1), which is increased in hypoxia and induces trophic changes in the cavernosal smooth muscle.

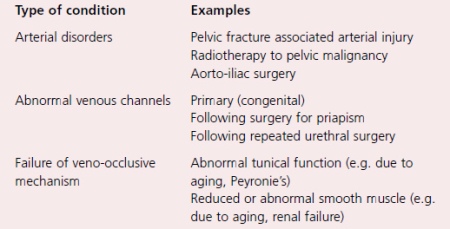

In addition to atherosclerosis, other disorders of both the arterial supply and the venous drainage of the penis can result in ED, and examples of both.

When there is failure of the veno-occlusive mechanism, the phenomenon of venous leakage occurs. This is a purely radiological phenomenon seen during specialised radiological imaging of the penis (cavernosography). When originally described, it was thought that the abnormal veins represented the primary pathological pathological abnormality, and for some years surgical ligation of these veins was undertaken as a means of treating ED. However, with the understanding that the venous leak was almost always secondary to abnormalities of the tunica albuginea or to disease of the cavernosal smooth muscle (and with the realisation that the results of venous surgery were poor), surgical treatment has almost completely disappeared.

Cellular causes of erectile dysfunction

Two types of cavernosal cells are central to penile erection; namely smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells. The vascular endothelial cells line the trabecular spaces of the cavernosal sinusoids and release a variety of vasoactive chemicals which control smooth muscle tone within the penis. The most important of these is NO. Diseases which damage the endothelium impair the vascular response of the penis to neural stimuli. A number of diseases damage the endothelium, including hypercholesterolaemia, but the most important is diabetes mellitus.

The structural changes in the endothelium that are produced by diabetes are accompanied by functional changes that result in impaired smooth muscle relaxation.

The diseases of smooth muscle that can result in erectile dysfunction have already been alluded to above. Aging results in reduced penile smooth muscle, as does atherosclerosis, while renal failure results in smooth muscle dysfunction. When the smooth muscle malfunctions, arterial dilatation is incomplete, cavernosal relaxation fails to occur and the veno-occlusive mechanism fails.

Neurogenic erectile dysfunction

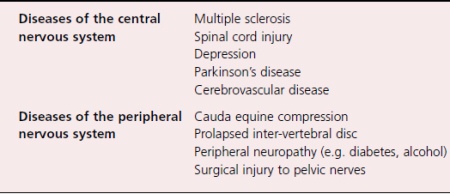

Diseases of both the central and the peripheral nervous system can result in erectile dysfunction. Again, there are too many to allow much detailed discussion and a list of the commoner neurogenic causes of ED.

Several psychiatric conditions, such as depression, can result in ED, and they are more usefully considered as organic causes rather than psychogenic. In fact, the relationship between depression and ED is a complex one. Depression can certainly result in ED, but mild depression can also result from ED, such that it has become clear that treatment of ED in men with mild depression can improve the depressive symptoms as well as the ED. A further issue is the sexual effect of the drugs used to treat depression (see later).

Spinal cord injury affects erectile function, but the picture depends upon the level and extent of the injury. Broadly speaking, men with high lesions can still get reflex erections (via intact reflex pathways) while men with low cord lesions can sometimes continue to get psychogenic erections (via intact sympathetic pathways).

Other issues that are relevant in men with neurological disease are the effects of the disease upon mobility, manual dexterity and urinary function. Disorders of one or all of these systems might also exacerbate any erectile dysfunction. Nowhere is this seen more clearly than in multiple sclerosis, where quite severe disability can be seen in young men who might have relatively normal sexual function. Furthermore, even if erectile function has been lost, but can be restored by treatment, other disabilities might preclude sexual activity.

Endocrine mechanisms of erectile dysfunction

Testosterone is central to normal male sexual function having an important role in both sexual drive and penile erection. However, a reduced level of testosterone has variable effects upon sexual function. There is reduction in libido, but a less marked effect upon erectile function. Men who are hypogonadal do not necessarily lose psychogenic and reflex erections. They do, however, have diminished nocturnal erectile activity, with both reduced duration and rigidity of the erection.

Again, there is a large number of causes of reduced serum testosterone, but they can be broadly classified into primary hypogonadism (where the disease is testicular) and hypogonadatrophic hypogonadism, where the primary disease affects the pituitary or the hypothalamus.

- Examples of the former are the hypogonadism which may follow mumps orchitis, or that which follows radiotherapy to the testes.

- Examples of the latter include congenital causes such as Kalmann’s syndrome and acquired causes such as pituitary tumours.

A rare endocrine cause of ED is a prolactin secreting tumour of the pituitary. The presenting symptoms are typically ED, galactorrhea and gynaecomastia.

The serum testosterone is usually reduced and the diagnosis is made by CT scanning of the pituitary.

Modifiable Factors

Obesity is associated with decreased levels of testosterone and free testosterone and increased peripheral conversion of testosterone and other androgens to oestrogen. Weight loss may therefore influence testosterone levels.

A randomised single-blind trial of 110 obese men aged between 35 and 55 years without diabetes, hypertension or hyperlipidemia and who had ED with an IIEF score of 21 or less were assigned to either advice to achieve a loss of 10% or more of their total body weight by reducing calorie intake and increasing physical activity or a control group who were given general information about healthy food choice and exercise.

Lifestyle changes were associated with improvement in around one third of obese men with ED at baseline.

for treat ED we have good remedy – Cheapest Viagra in Australia

– High body mass index may be related with sleep apnoea which is itself associated with ED. Treatment with continued positive airway pressure to the nasal passages improves erectile function.

A recent comprehensive evaluation identified via a Medline search until July 2007 supports the association between metabolic syndrome, ED and low-grade inflammatory state. The increased circulating levels of inflammatory and endothelial-prothrombotic compounds are related to the presence and severity of ED. Specific inflammatory biomarkers and their combination appear to have the potential to aid the diagnosis or exclusion of ED. It is concluded that ED and coronary artery disease may confer a similar unfavourable impact on the inflammatory and prothrombotic state and that ED adds an incremental activation in addition to coronary artery disease. Lifestyle and risk factor modification as well as pharmacological therapy are associated with anti-inflammatory effects.

– A Mediterranean style diet has been shown to lead to an improvement of erectile function score (IIEF-5) after 2 years with around one third of men regaining normal erectile function with a significant improvement in endothelial function score and inflammatory markers (hsCRP). As noted, Esposito reported that the loss of total body weight by greater than 10% and the increase in physical activity led to an improvement in the IIEF-5 score and reduction in serum concentrations of IL-6 and hsCRP after 2 years. The potential role of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors, statins and ACE inhibitors are considered further by Vlachopoulos et al.

– Smoking cigarettes increases the risk of cardiovascular disease which in turn is associated with ED. A recent article supports the association between ED and smoking cigarettes. The controversies regarding the association between smoking and ED are considered further in this article. Nicotine is also a potent vasoconstrictor and for those people with compromised arterial function the immediate effect of smoking a cigarette persists for at least 2 h.

– The role of illicit substance abuse is a further factor where lifestyle change can have a marked impact on ED. Lifetime use of ED medications was reported as used in a quarter of men surveyed in a substance abuse treatment outpatient clinic.

Psychological and Psychosexual Couple Interventions

The role of psychological treatments in conjunction with physical treatments remains an area of controversy and debate. For many men, there is an inevitable psychological cognitive or emotional response to a failure to achieve or maintain a rigid erection which he considers essential to have satisfactory sexual intercourse either alone or with his partner.

For some men there may be a wholly psychological contribution towards the ED. In either case, there is often a rejection of the suggestion that engagement in psychological or talking therapies will bring benefit to the man and his partner. For some patients, it is helpful to demonstrate the presence of an adequate erection. This has included the use of a pharmacological induced erection within the clinic (for example using intra-cavernosal alprostadil) or by using other evidence to demonstrate erectile capacity. Use of partner recall can be helpful but in other circumstances objective measurement such as nocturnal RigiScan or ultrasonography demonstrating excellent function is required before the patient agrees to engage in a talking therapy Australian Viagra Sales.

The literature is sparse for randomised control trials as the primary or secondary treatment for ED. With this in mind the interested reader is referred to a recent article which reviewed the various psychological and theoretical frameworks and review of literature for the use of talking therapies for ED. A recent Cochrane review of psychosocial interventions for ED found evidence that group therapy improves ED in selected patients who received group therapy, and sildenafil showed significant improvement of ED. Men were less likely than those receiving only sildenafil to drop out.

Lithium

Although there has been extensive study of antidepressant-associated sexual side effects in patients with depressive disorders, there has been very little investigation into patients treated with lithium for bipolar disorder or unipolar depression.

A small open-label study of bipolar and schizoaffective male patients taking lithium as their only medication, found that 31.4% reported sexual dysfunction on a sexual function questionnaire. Patients were all reportedly euthymic at the time of inquiry. Just over 23% of patients reported reduction in frequency of sexual thoughts and 20% of men reported loss of erection during sex. Maintaining erections were reported by 14% of patients. Despite these problems, almost all patients reported normal pleasure during sexual activity and were satisfied with their sexual performance. Serum lithium concentrations were similar between patients with and without sexual dysfunction. Overall, patients reported that sexual dysfunction was minor, did not lead to noncompliance, and was not a source of distress. Viagra professional Australia

A point prevalence evaluation of patients with bipolar disorder found similar results, suggesting that patients treated with lithium as their only medication infrequently experience sexual dysfunction. In this study, 104 patients with bipolar disorder (nearly all of whom were euthymic) were asked to rate the current effects of lithium on sexual functioning ‘relative to a period of normal mood when the patient was not taking lithium.’ Several parameters of sexual function were rated according to the change affected by lithium, rated as ‘none, mild, moderate or great’. The authors found that among patients taking monotherapy lithium, only 14% of patients reported sexual side effects and these were almost all mild. The type of sexual side effect was not detailed for lithium. On the other hand, when lithium was combined with benzodiazepines, rates jumped to 40% of patients, and many of the complaints were moderate or great. This study has a number of limitations, principally that ratings were made retrospectively, sometimes many years after starting lithium. The study had no control group and medication was not randomly assigned. If the benzodiazepines indeed caused sexual problems, it is not clear if they caused them independently of lithium or if in combination with the lithium.

Finally, one recent study, published in Italian, reported that ‘clinically stable’ patients with bipolar disorder taking lithium were more likely than age-matched healthy controls to report to have ‘never’ or ‘rarely’:

- sexual intercourses (45% vs. 20%),

- sexual fantasies (25.4 vs. 13.6%),

- desire (37.3 vs. 9.5%).

It is unknown from this study how much the patient’s mood disorder or medication treatment contributed to their sexual complaints.

Hence, there has been very limited study into the effects of lithium on sexual functioning, though lithium appears to have limited adverse sexual side effects. Further prospective studies are needed.

To pursue appropriate treatment, it is essential that providers assess the patient’s complete sexual functioning. This requires a thorough understanding of the nature of sexual dysfunctions, the factors involved in their development, and the means to assess sexual functioning on a variety of levels. Informing patients about treatment options, including the option of no treatment, is an important step in the assessment process. This needs to be handled very sensitively as the clinician does not want to inordinately sway the patient toward or away from treatment. Instead, the clinician should help the client or couple rationally weigh the relevant information to make a good decision for them.

It is important to note that patients with underlying psychopathology may respond poorly to sex therapy. Possible treatment plans for patients suffering from psychopathology in conjunction with a sexual dysfunction include

- initially treating the primary mental disorder followed by sex therapy,

- treating the mental disorder and the sexual dysfunction simultaneously,

- only treating the mental disorder,

- only treating the sexual dysfunction.

If the sexual dysfunction is not the primary problem, then a sexual dysfunction diagnosis is not appropriate, thus, making the fourth alternative listed above unfit.

Lobitz and Lobitz) suggest that the decision to treat the sexual dysfunction in light of observable psychopathology involves two criteria:

- the problem does not greatly interfere with the person’s everyday functioning,

- the problems should not be likely to interfere with treatment.

– This first criterion is problematic considering that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revised (DSM-IV-TR) requires that a problem cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty for it to be considered a mental disorder.

– The second criterion seems more relevant as it guides treatment providers in determining the severity of the psychopathology and its relevance to the sexual dysfunction (i.e., whether it is a cause or result of the other mental disorder).

For example, it has been suggested that depression affects those areas that control sexual functioning and decreased activity in these areas results in sex dysfunction.

McConaghy purports that most clinicians, regardless if they label it as such, deliver therapy that is cognitive–behavioral in nature and based on Wolpe’s conceptualization of sexual dysfunctions as resulting from anxiety about one’s sexual performance. In their review of empirical studies investigating the validity of treatments of sexual dysfunction, Heiman and Meston asserted that all of the empirically supported treatments are based on a cognitive–behavioral treatment model and the most frequent components in these treatments were sensate focus and systematic desensitization. More recently, O’Donohue et al. also conducted a critical review of empirical studies evaluating the effects of psychotherapy for male sexual dysfunction. Eighty percent of the obtained publications did not meet the reviewer’s inclusion criteria. They suggest that while clinicians maintain that treatments for male sexual dysfunction are efficacious, the lack of methodologically sound research in this area disallows claims regarding empirical validity.

Many studies examining the efficacy of sex therapy techniques have failed to employ control groups. Instead, they have compared treatment groups that have commonly integrated components from different techniques. For example, Everaerd and Dekker compared a treatment group that included sensate focus, sexual stimulation exercises, and the squeeze technique when premature ejaculation was present against a different treatment group that involved in vivo and in vitro systematic desensitization. In this study, the majority of couples in both groups showed some improvement; however, the research design makes it difficult to make any claims about what specific treatment was effective or the appropriateness of specific treatments for particular problems. Currently, difficulties in making inferences are attributable to methodological shortcomings rather than treatment inadequacies.

Despite the paucity of rigorous empirical research, clinicians continue to deliver treatments for sexual dysfunctions. Treatments ought to be tailored to the cause of the specific problem rather than to the particular diagnosis. In other words, males suffering from similar sexual dysfunctions (i.e., meeting the same DSM diagnostic criteria) may benefit from treatments that address different causes (e.g., anxiety vs. lack of ejaculatory control). The effort to deliver appropriate treatments for sexual problems is thwarted by the fact that the detection of psychological agents that cause and maintain sexual dysfunctions remains unclear; however, because normal sexual functioning affects an individual’s and couple’s quality of life, mental health providers can utilize current knowledge about possible etiological variables, the few existing psychometrically sound assessment instruments, and theore tically informed treatments that are likely efficacious for valid causal pathways. These treatments that are based on a cognitive–behavioral model will be discussed below. Or you can use Viagra New Zealand to treat ED.

Penson et al. analyzed the data from the large Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study which included 1,213 men who underwent prostatectomy for prostate cancer. They reported on urinary and sexual outcomes at up to 5 years postopera- tively. Compared to baseline rates of 81% with erections firm enough for penetration, rates at 6, 12, 24 and 60 months were 9, 17, 22, and 28% respectively. Notably, the data was collected on men diagnosed from 1994 to 1995 and the 60 month survey was distributed in 2000. Thus, all patients theoretically were exposed to intracavernous injection in the early postoperative period, but sildenafil was not available until around 3 years postoperatively. Consequently, this provides a relatively good estimation of the natural history of erectile dysfunction post- prostatectomy, though the improvement in erec- tile function seen between years 2–5 could have been significantly affected by the introduction of PDE5 inhibitors. Indeed, 43% of the study patients had used sildenafil at least one time and of these 520 patients, 32% reported achieving an erection suitable for intercourse. Of the technologies available around the beginning of the study, intracavernous injection was tried by 17%, vacuum erection devices were tried by 25%, “other” therapies including MUSE™ were used in 7%, and penile prostheses were implanted in 4% of the men.

Treatment of erectile dysfunction in post-prostatectomy men is unique compared with ED caused by other factors; in that rehabilitation (ED recovery) from treatment induced nerve and vascular injury are plausible. Thus, treatment of post-prostatectomy ED must keep two goals in mind: immediate erectile function facilitated by medication use and ultimate return to pre-pros- tatectomy erection status without use of adjunctive medications.

Penile injections do not require neuronal integrity to function. Injections have been shown to have the highest functional erection success rates following RRP with multiple studies showing ³90% efficacy at 6 months post-op. Like penile injections, MUSE™ works independent of nerve status. This medication has been shown to be effec- tive in men with ED after RRP, producing an erection thought to be sufficient for intercourse in the clinic in 70% of subjects, and leading to successful intercourse at home in 40% of subjects compared to 7% in placebo. Similar results were found in a study where 55% of subjects had successful intercourse and 48% effectively used MUSE™ long term (2 years) after RRP.

The potential to regain some erectile function with time (typically maximized at 18–24 months) after radical prostatectomy is well established in the literature. The potential of pharmacotherapy to aid in return to pre-op, baseline erectile function status with return of spontaneous, medication unassisted erections adequate for penetration is not only theoretically intuitive, but also has been reported in numerous small studies. The theoretical support is drawn from the results of denervating the cavernosum of rats and observation of the ensuing hypoxia and fibrosis coupled with the knowledge that erections increase the oxygenation of the cavernosum.

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors are likely the most commonly used rehabilitative pharmaceutical though they have lower theoretical rehabilitative potential than ICI or MUSE™ as they require a threshold level of neural integrity to be effective. McCullough et al. published a study using 50 and 100 mg nightly doses of sildenafil followed by an 8 week washout period. This study showed that men on daily sildenafil treatment had much higher rates of erectile function than those taking placebo, namely 24% for 50 mg sildenafil and 33% for 100 mg sildenafil versus 5% for placebo. Rates of return to spontaneous erection with ICI and MUSE™ should theoretically be higher because they are more effective at producing erections during the neurapraxic period post pros-tatectomy. Montorsi et al. published one of the first papers on erectile rehabilitation comparing 3 months of t.i.w. ICI alprostadil to patients receiving no treatment. Patients were assessed at a 6 month follow up, i.e. after a 2 month period without t.i.w. alprostadil. Eight (67%) were noted to have return of spontaneous erection which only required the use of ICI alprostadil one in 4.2 times for successful intercourse. The other four patients in the ICI group reported needing to use ICI greater than 50% of the time to achieve successful intercourse.

Only 20% of the placebo group reported spontaneous erections that were sufficient for intercourse. This study, although often cited, likely suffers from methodological flaws as no other studies have replicated these impressive results. A larger study by Mulhall et al. examined a group of men with functional preoperative erections prior to prostatectomy and who were non-responders to sildenafil in the early post- operative period. At 18 months postop, men who followed a regimen of t.i.w. ICI were compared to those who did not follow the protocol. Of the 58 men in the protocol group, 52% had a return of spontaneous erections compared to 19% of the 74 men in the non-protocol group. Althoughencouraging, this study suffers from a high degree of self selection bias, as the patients who were not hav- ing success and ultimately stopped treatment, but adhered to follow-up were simply included in the non-protocol group. The efficacy of MUSE™ in penile rehabilitation has also been tested. Raina et al. reported on 97 men post-prostatectomy, 56 of whom used t.i.w. MUSE™ for 6 months and 35 of whom used only p.r.n. erectile aids. Those who used MUSE™ attained a fourfold higher rate of spontaneous erections than those who did not (40% vs. 11%).