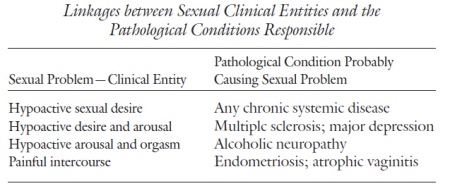

Application of the disease perspective to sexual disorders is the work of ensuring that the somatic factors, disease processes, and physiological functions, as they may relate to the cause or expression of the sexual disorder or dysfunction, have been identified. It entails linking the clinical entities with a pathological condition. In sexual problems, the clinical entities of the sexual dysfunction and the patient’s medical history may indicate the pathological condition. The linking of the two is the task of the disease perspective. Table lists some common linkages between sexual problems (clinical entities) and medical illnesses (pathological conditions).

Treatment in the disease perspective is to cure the disease or, when that is not possible, to alleviate the symptoms. When sexual dysfunction is present as a helpful sign or symptom (clinical entity) of an underlying pathological condition, treatment is given to address the pathological condition. When one cannot successfully treat the underlying condition (e.g., peripheral neuropathy), symptomatic treatment is given (e.g., oral medication for erectile function). Another clinical case can illustrate the work of the disease perspective.

■ Ralph was a 45-year-old man who had enjoyed a twenty-year marriage with his wife. Their three children, now in their teens, added no more than the usual amount of Sturm und Drang of adolescence to the household. Ralph had been in sales throughout his career and presently was making another shift in employment—this time to assume major responsibility for a national product line.

Ralph was in apparent good health, although slightly overweight. He drank one beer daily with his main meal and exercised infrequently. In their sexual life, Ralph and his wife had usually had intercourse about three times a month and neither had experienced sexual dysfunction—until recently.

For the past several months, Ralph had noticed himself becoming less and less interested in sex. The frequency of intercourse had decreased, and he had not wanted to have sex for the past two months. Sexual thoughts and fantasies were absent. While he had masturbated on occasion in the past, this behavior was absent in the past six months. He noticed that he and his wife were not getting along as well as usual, and more frequently than in the past were “getting on each other’s nerves.”

Ralph consulted his physician, who ordered a serum testosterone level and liver function tests on the suspicion that Ralph had underreported the amount of his drinking and, in fact, may have reduced testosterone due to his alcohol consumption. The physician also assessed Ralph for depression. Other than being upset by his low libido, Ralph gave no indication of being clinically depressed. Even the strain of the transition to the new position at work was evoking in Ralph his typical “can do” optimism.

The serum testosterone level came back remarkably low. This explained the low sexual desire. But more remarkably, the pituitary (prolactin) level, measured at the same time, was correspondingly elevated. Ralph’s physician suggested that he have an MRI to check for any lesion on his pituitary gland that might be causing the hyperprolactinemia.

The MRI reading came back positive. Ralph had a pituitary adenoma, a nonmalignant neoplasm on his pituitary gland. He began a regimen of bromocriptine. After several months’ treatment, his levels of prolactin and testosterone had returned to normal. With the return of normal levels, Ralph regained his premorbid baseline of intercourse once a week.

Two years later, Ralph and his wife are back to enjoying sex at a frequency of about once every ten days; he has again switched to another company; and only one of the three children has gotten into academic trouble. In short, things are back to normal.

The disease perspective is the perspective most often used by physicians. For this reason, application of the disease reasoning process to psychiatric or behavioral disorders is often referred to, disparagingly, as the “medicalization” of psychological problems. Is this a fair critique?

If, in fact, the disease perspective is the only reasoning method in the mental health clinician’s armamentarium, then his or her diagnostic reasoning will be reductionistic. But attempting to understand all problems as ultimately rooted in a bodily disease is not the disease perspective’s rationale. As I will repeat often in this book, a particular perspective—in this case, the disease perspective—is but one way to understand and sometimes even causally explain a disorder. Ralph’s case is a good example of this.

Ralph’s low libido was the symptom that disturbed him (and his wife) and alerted the physician. He clearly was not as interested in either thinking about or having sex as he had previously been. While Ralph’s low desire might have been attributed to a combination of aging, alcohol consumption, pressure at work, and tension at home, his physician ordered the proper tests. The low serum testosterone was the abnormal hormonal function responsible for his reduced sexual desire.

The physician then sought to explain why the testosterone level was so low. He discovered that high prolactin levels, hyperprolactinemia, were suppressing it. But what was the underlying cause of the high prolactin? The MRI indicated that a small, benign tumor—an adenoma— was growing on Ralph’s pituitary gland, located deep within the subcortical area of his brain. Fortunately, surgery was not indicated and Ralph responded well to the oral medication. If the disease perspective had not been employed here as the primary diagnostic and treatment perspective, then an expenditure of many months and dollars, and perhaps a further deterioration of the relationship between Ralph and his wife, might have followed. Hours of sexual or marriage counseling might have been spent on asking how much did Ralph really drink, were husband and wife taking each other for granted and not communicating well, was Ralph too involved in his work? While all these questions might be worthy of attention, it would have been a major therapeutic error to think that addressing them and attempting to make changes in these areas could have any substantial effect on Ralph’s sexual desire. In addition to low libido, therapy-induced frustration would have been added to the symptom cluster.