Drugs (medically prescribed, alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, illicit drugs) are consumed to cure, to calm, to stimulate, or to avoid physical and psychological pain. The body affected by drugs is a body with altered sexual responsiveness. Therefore, ingested drugs must be recognized as possible causes of sexual dysfunctions and disorders.

Some drugs are alleged to be prosexual in that they are thought to promote sexual activity. Alcohol, cocaine, and hallucinogens, including amphetamines, fall into this grouping.

– Alcohol is popularly thought to decrease inhibitions about sexual activity. In fact, several researchers over the decades have generally concluded that alcohol has negative physiological effects on arousal and orgasm, to say nothing of the severe health effects that can result from sustained alcohol abuse. But the expectations of both women and men are such that they report increased sexual functioning, even when responding to an alcohol placebo. Thus, the frequent clinical situation is that patients generally believe that alcohol helps them to function sexually, while in fact both its short-term and long-term effects on healthy sexual functioning may be the opposite.

– Cocaine is a drug of abuse that is often linked with sexual behavior. As is often the case with alcohol intoxication, cocaine impairs judgment and often leads to sexual activity that puts individuals at risk for sexually transmitted diseases. Cocaine’s dopaminergic effect increases sexual desire in both men and women but also inhibits orgasm and, given a sufficient dosage, causes erectile dysfunction. Individuals with a cocaine habit will find themselves with increased sexual desire, with little inhibition about the sexual activity, and eventually unable to become aroused.

– Hallucinogens such as LSD, Ecstasy, mushrooms, and amphetamines are commonly perceived to be aphrodisiac in their effect on sexual function. This might be expected given the CNS effects caused by these substances. As Crenshaw and Goldberg noted, “The intoxicated states (however mystical) that occur with hallucinogens involve severe alterations in dopamine, serotonin and excitatory amino acid activity. Phencyclidine (PCP, angel dust), for example, incites potent activity at glutamate receptors, apparently inducing psychoses by altering excitatory amino acids. Given the strong impact of these neurotransmitters on sexual function, both extremely positive and negative sexual effects may be expected to occur.” Relying on intoxication for sexual experience has obvious detrimental long-term consequences.

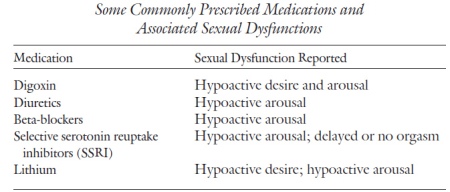

– Other drugs are decidedly negative in their effects on sexual functioning. Excessive alcohol, chronic nicotine use that has caused cardiovascular disease, some antihypertensives, and many antidepressants—all have been implicated in interfering with sexual function. Table lists some of the more commonly prescribed drugs and their effects on sexual function. This not an exhaustive list, but it provides examples of the reported sexual dysfunctions associated with the drugs.

Given the various effects that drugs can have on the physiological basis of sexual function, the clinician needs to know what drugs the individual with a sexual problem is taking. A complete review of a patient’s use of prescribed, over-the-counter, and possible illegal drugs is essential. Once known, the drugs should be examined for their possible contributory role in the sexual problem.

Psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia are as much the result of disease processes as are somatic diseases such as pituitary adenoma or tuberculosis. As such, they deserve the same diagnostic strategies and consideration of appropriate somatic treatments (e.g., medication). Most of these psychiatric diseases affect a patient’s sexual functioning.

In the initial diagnostic stage of treatment, the disease perspective alerts the clinician to exhaust empirical medical data provided by the presenting problem and gathered in the patient’s history. A recent physical examination is necessary for any disorder that may have somatic roots. Dr. M.’s knowledge of Sally’s behavior was grounded in a careful history taking, which indicated that a major mental illness had afflicted the patient’s mother. While certainly the illness could have affected the mother-daughter relationship in many ways (e.g., making the mother less emotionally available), Sally’s bipolar disorder might also have genetic components.

The disease perspective correspondingly alerts the clinician not to rush prematurely to establish an etiology rooted in a “meaningful explanation” of the problem. For example, it would be facile to attribute Sally’s behavior to some fault in the marriage or to personality factors such as inappropriate dependence on male approval. Indeed, almost all depressed individuals attribute their depression to life situations, in an understandable attempt to develop a rationale for the way they feel. It is much easier to say “I am depressed because of the way my life has gone recently” than to say “While things have not been perfect, all in all everything has been going as it usually does. It is just that my depressed mood has a life of its own. My neurotransmitters must not be working properly.” The former is an attempt at a meaningful explanation (to be examined in the life story perspective), while the latter is a (rarely heard) appreciation of the depression from the disease perspective.

The disease perspective is, as would be expected, the main perspective of schools of medicine and nursing. These graduate programs stress the need to observe carefully and exhaustively the various somatic phenomena in a person’s complaint as well as the medical history that he or she provides. Medical graduate programs teach their future clinicians how to conduct a review of organ systems and mental status examinations. Personal and family medical histories yield information about past diseases, surgeries, and medications.

Graduate schools of psychology and social work often do not share this emphasis. In these disciplines, the circumstances of intrapsychic, interpersonal, and social environment are valued highly and therefore often described in minute detail. Attention may be paid to personal and family medical and psychiatric histories. There is less likely to be a recording of the complete regimen of medications with accurate dosage. And conducting a mental status examination—with its attention to factors such the patient’s appearance, neurovegetative symptoms, manner of speech, thought processes—is usually an indication that the psychologist or social worker has been trained in a medical or residential facility.

Whereas medical and nursing students may overlook the psychological and relational factors in the patient’s disease, social science students, especially with the advent of social constructionism, may overlook the role of the body and the body’s diseases in the etiology of the problem. The disease perspective, then, is the familiar territory of the physician, nurse, and medical clinician. It is the terra incognita of the psychologist, social worker, and counselor, unless efforts are made to learn more of this “body” of knowledge. Thus, the role of the disease perspective should be supported and nurtured by the psychologist, social worker, and counselor by developing relationships with medical practitioners, including psychiatrists, who can supplement their psychological skills with medical knowledge of the body and its diseases.

It is not always easy to see the connection between a sexual behavioral pattern and a disease process. Often this is because we notice the behaviors as a syndrome and correlate them with a psychiatric disorder that is not yet proven to have a pathological process in the body (brain). The case of Sally is helpful here.

Sally was a 43-year-old married woman whose husband was employed as a utility repairman. It was the second marriage for him and the third marriage for her. Together they had no children, but she had two daughters (ages 20 and 18) and he had a son (age 14) by previous marriages. She worked as a clerical staff person in a construction company.

They sought marriage counseling in crisis because Sally had had a sexual relationship with a neighbor, the father of one of her stepson’s friends. In the initial history, Sally reported that she had always felt she had a higher sexual drive than other women she knew. She judged herself to be slightly better than average in appearance, and she thought she often “gave off vibes” to men that she was sexually interested in them, even though they had met only casually. She said that men usually responded to her, and it was not difficult to conclude a casual meeting with a sexual encounter. Sally judged that she had had approximately thirty to thirty-five sexual partners in her life, all of them men, except once when she engaged in a mйnage а trois with a man and a woman.

Sally described most of the sex as involving little knowledge of the other person but very intense in terms of sexual drive and pleasure. She felt that the men were interested in sex also and that neither they nor she sought any lasting or committed relationship. She said she loved her husband and did not want the recent sexual wandering to ruin the marriage as it had in the two previous marriages. She wanted this time to be different and was convinced that it would be.

In her initial history-taking session with Sally, Dr. M. took a complete and careful sexual history and a detailed mental status examination. From both the history and the present mental status, Dr. M. concluded that Sally’s episodic high drive correlated with other symptoms of a bipolar II disorder.

On closer examination of the sexual encounters, Sally was able to see that there was an episodic quality in the frequency of the behaviors. For months she would have what she felt was low (for her) sexual desire and interest, and then a period ranging from four to six weeks when she would become, in her words, “sexually alive.” Also during these periods of being sexually alive, Sally would have a great deal of energy, undertaking exercise programs, requiring little sleep because of all she wanted to accomplish, and, on occasion, spending to such a degree that she “maxed out” her three credit cards. During these periods, she felt as if she got along very well with her husband, although the spending caused arguments.

Sally could not describe her mood and energy level during the times between these periods of elevated mood and energy. The best she could do was to say, “It’s kinda like I feel now, since the discovery of my sexual time with N.” In the mental status examination of her present mood, Sally reported that she felt tired and was not sleeping well—which she attributed to her worries that the marriage might be breaking up. She had lost eight pounds in the past month and wanted sex with her husband only to help keep the marriage going, not because of any sexual desire or interest on her part. While she felt somewhat guilty about the sex with her neighbor, it was difficult for her to distinguish the guilt about the behavior itself from the deep regret that the trysts were discovered and her marriage threatened.

Dr. M. learned other facts about Sally that confirmed her diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. Although Sally had never received treatment from a psychiatrist or other mental health provider, her mother had been hospitalized on three occasions. The first time occurred in her mother’s early twenties and the diagnosis was schizophrenia. The last two hospitalizations had occurred within the past twenty years, and her mother was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and alcohol abuse. For the past seven years her mother had done well, avoiding alcohol and being maintained on a regimen of lithium carbonate and, more recently, Depakote (valproic acid) to keep her mood stable.

With the familial factor of affective illness, and the carefully obtained psychiatric history, Dr. M. concluded that Sally’s sexual behaviors were caused, in large part, by her affective illness. The bipolar II disorder increased her libido and diminished her ability to judge the appropriateness of her behaviors, both sexual and financial. At the time of her sexual escapades, Sally clearly had only a vague awareness of the consequences that her behaviors might have on her life and on the relationships she valued.

Dr. M. recommended both psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment. Because Sally’s mother responded well to Depakote, Dr. M. started Sally on that medication, in addition to a serotonin-specific antidepressant for her present depression. The psychotherapy had two goals: to understand Sally’s vulnerability to the excesses of bipolar disorder and to “make some sense” of the prolific sexual experiences she had had in her life.

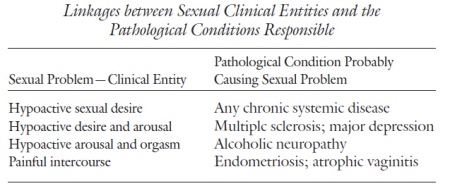

Application of the disease perspective to sexual disorders is the work of ensuring that the somatic factors, disease processes, and physiological functions, as they may relate to the cause or expression of the sexual disorder or dysfunction, have been identified. It entails linking the clinical entities with a pathological condition. In sexual problems, the clinical entities of the sexual dysfunction and the patient’s medical history may indicate the pathological condition. The linking of the two is the task of the disease perspective. Table lists some common linkages between sexual problems (clinical entities) and medical illnesses (pathological conditions).

Treatment in the disease perspective is to cure the disease or, when that is not possible, to alleviate the symptoms. When sexual dysfunction is present as a helpful sign or symptom (clinical entity) of an underlying pathological condition, treatment is given to address the pathological condition. When one cannot successfully treat the underlying condition (e.g., peripheral neuropathy), symptomatic treatment is given (e.g., oral medication for erectile function). Another clinical case can illustrate the work of the disease perspective.

■ Ralph was a 45-year-old man who had enjoyed a twenty-year marriage with his wife. Their three children, now in their teens, added no more than the usual amount of Sturm und Drang of adolescence to the household. Ralph had been in sales throughout his career and presently was making another shift in employment—this time to assume major responsibility for a national product line.

Ralph was in apparent good health, although slightly overweight. He drank one beer daily with his main meal and exercised infrequently. In their sexual life, Ralph and his wife had usually had intercourse about three times a month and neither had experienced sexual dysfunction—until recently.

For the past several months, Ralph had noticed himself becoming less and less interested in sex. The frequency of intercourse had decreased, and he had not wanted to have sex for the past two months. Sexual thoughts and fantasies were absent. While he had masturbated on occasion in the past, this behavior was absent in the past six months. He noticed that he and his wife were not getting along as well as usual, and more frequently than in the past were “getting on each other’s nerves.”

Ralph consulted his physician, who ordered a serum testosterone level and liver function tests on the suspicion that Ralph had underreported the amount of his drinking and, in fact, may have reduced testosterone due to his alcohol consumption. The physician also assessed Ralph for depression. Other than being upset by his low libido, Ralph gave no indication of being clinically depressed. Even the strain of the transition to the new position at work was evoking in Ralph his typical “can do” optimism.

The serum testosterone level came back remarkably low. This explained the low sexual desire. But more remarkably, the pituitary (prolactin) level, measured at the same time, was correspondingly elevated. Ralph’s physician suggested that he have an MRI to check for any lesion on his pituitary gland that might be causing the hyperprolactinemia.

The MRI reading came back positive. Ralph had a pituitary adenoma, a nonmalignant neoplasm on his pituitary gland. He began a regimen of bromocriptine. After several months’ treatment, his levels of prolactin and testosterone had returned to normal. With the return of normal levels, Ralph regained his premorbid baseline of intercourse once a week.

Two years later, Ralph and his wife are back to enjoying sex at a frequency of about once every ten days; he has again switched to another company; and only one of the three children has gotten into academic trouble. In short, things are back to normal.

The disease perspective is the perspective most often used by physicians. For this reason, application of the disease reasoning process to psychiatric or behavioral disorders is often referred to, disparagingly, as the “medicalization” of psychological problems. Is this a fair critique?

If, in fact, the disease perspective is the only reasoning method in the mental health clinician’s armamentarium, then his or her diagnostic reasoning will be reductionistic. But attempting to understand all problems as ultimately rooted in a bodily disease is not the disease perspective’s rationale. As I will repeat often in this book, a particular perspective—in this case, the disease perspective—is but one way to understand and sometimes even causally explain a disorder. Ralph’s case is a good example of this.

Ralph’s low libido was the symptom that disturbed him (and his wife) and alerted the physician. He clearly was not as interested in either thinking about or having sex as he had previously been. While Ralph’s low desire might have been attributed to a combination of aging, alcohol consumption, pressure at work, and tension at home, his physician ordered the proper tests. The low serum testosterone was the abnormal hormonal function responsible for his reduced sexual desire.

The physician then sought to explain why the testosterone level was so low. He discovered that high prolactin levels, hyperprolactinemia, were suppressing it. But what was the underlying cause of the high prolactin? The MRI indicated that a small, benign tumor—an adenoma— was growing on Ralph’s pituitary gland, located deep within the subcortical area of his brain. Fortunately, surgery was not indicated and Ralph responded well to the oral medication. If the disease perspective had not been employed here as the primary diagnostic and treatment perspective, then an expenditure of many months and dollars, and perhaps a further deterioration of the relationship between Ralph and his wife, might have followed. Hours of sexual or marriage counseling might have been spent on asking how much did Ralph really drink, were husband and wife taking each other for granted and not communicating well, was Ralph too involved in his work? While all these questions might be worthy of attention, it would have been a major therapeutic error to think that addressing them and attempting to make changes in these areas could have any substantial effect on Ralph’s sexual desire. In addition to low libido, therapy-induced frustration would have been added to the symptom cluster.